Is it legitimate to use other authors works in order to create a new piece of art? The US Supreme Court will issue a ruling that could change the way contemporary art has created one of its most iconic works.

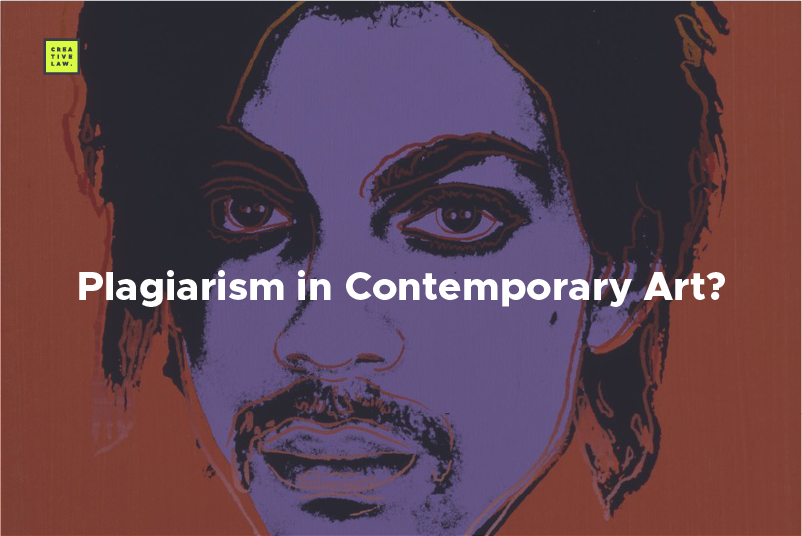

“Appropriationism”, the artistic movement in which an artist uses elements from others to create his work, has been one of the pillars of creation in postmodern art. Since the end of the ’70s, this type of practice has reached the point where it borders the limits of what is legal. One of the greatest representatives of contemporary art, Andy Warhol, and the photographer Lynn Goldsmith are the protagonists of a case that puts this artistic technique in check. Is appropriation really a form of plagiarism?

In 1981, Warhol used the famous photography of the photographer Goldsmith to create the 16 color lithographs that make up his “Prince Series”. Goldsmith accuses that this work is a mere reproduction of his photography, therefore a plagiarism of his work, while for the artist and the Andy Warhol Foundation, this is a conceptual re-elaboration.

This dispute resulted in a lawsuit by the photographer, which the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in favor, establishing that Warhol’s use of the photographs does not constitute a “fair use” of them. The law firm Latham & Watkins, which represents the Andy Warhol Foundation, has requested the US Supreme Court to review the decision of the Court of Appeals on the grounds that it is necessary to guarantee and reaffirm the importance of freedom of artistic expression.

The so-called «Prince series» was made based on the photograph taken by Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. She gave the rights to the image to «Vanity Fair» magazine, for the publication of an illustration based on it for a 1984 issue. The magazine commissioned the realization of this illustration to Andy Warhol who, however, did not limit himself to executing the commission, but went further and created the set of illustrations and serigraphs that constitute the «Prince series». The photographer did not know of the existence of the Prince Series until 2016, coinciding with the death of the pop star and in which a part of the series was published as a tribute to the singer. And the carousel of demands began.

In 2019, Judge John G. Koetl ruled that Warhol did not make unlawful use of Goldsmith’s photography, as Goldsmith transformed the original image, adding “something new to the art world.” However, in March 2021, the Court of Appeals overturned this decision, arguing that “the fact that a work is transformative cannot simply depend on the intention of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic or judge may have. ». The importance of this declaration of the Court of Appeals is of extreme importance, since, with it, it is eliminating the “conceptual turn” experienced by art since the avant-garde. If the intentionality of an artist is not enough to declare something to be art, none of Duchamp’s “readymades” will reach such a category. If the expert interpretation of a critic is not enough to endorse the authorship of a certain work, the entire art edifice –and, with it, the so-called «institutional theory of art»– collapses. The judgment of the Court of Appeals constitutes such an ordeal to the art system that, from this moment, the old controversy of what art is will move from the artistic world to that of the courts.

What is relevant in this case is not the demand itself, but the “domino effect” that it could generate, with an unpredictable scope so far. To begin with, the same accusations that have been leveled against the «Prince Series» can also be extrapolated to other works by Warhol himself, whose gallery of portraits of great figures of pop culture is based on images of which he is not the author. Author. Pop art architecture itself would be completely dynamited, in what would mean a process of legal delegitimization of one of the most important artistic movements of the 20th century.

Other artistic reproductions such as Richard Prince, Jeff Koons or Sherrie Levine would be seriously affected by this ruling of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. During the 1970s, Richard Prince began what is, without a doubt, his most successful and acclaimed series: the one based on the appropriation of the image of the cowboy from the Marlboro tobacco company. Prince cropped and enlarged images of the cowboy published in magazines, presenting them as his own work that questioned the author’s theory and the principles of originality on which artistic creation has been based for centuries. In 1981, Sherrie Levine took it a step further with her “After Walker Evans” series. In it, the appropriationist artist limited herself to photographing some of the most famous works by the American photographer Walker Evans, without introducing any type of modification that could differentiate the copy from the original. Put the two side by side, it is almost impossible to establish which is Evans’s photograph and which is Levine’s appropriation. In this same decade of the 80s, Jeff Koons reproduced in porcelain, and on a large scale, cultural phenomena such as the Pink Panther or Michael Jackson. Neither the images nor its design were his own, since he could be another of those harmed by the controversial decision of the Court of Appeals.